To watch a talk about PRA by Dr. David Williams at the OCA Show on June 18th, click here .

Cathy Baxter – Kyashii Orientals

Introduction

Progressive retinal atrophy (PRA) is the umbrella term used to describe a group of inherited genetic diseases causing blindness in certain breeds of dog and, more rarely, in cats. PRA is characterised by the progressive degeneration of the retina, including cells within the retina called rods and cones. Rod cells detect shape and motion and function in low light. Cone cells detect colour and definition and function in bright light. Affected animals experience progressive loss of vision and ultimately blindness. They may also develop cataracts as a secondary complication. The condition in nearly all breeds of cat is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. Sadly, there is no treatment other than informed selective breeding to reduce the incidence of the condition.

Feline PRA

The breed of cat thought to be most affected by PRA is the Abyssinian, although the Somali and the Ocicat may be similarly affected. However, all associated breeds, which include Orientals and Siamese, may be at risk for PRA.

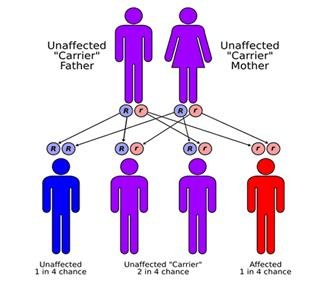

Two distinct forms of PRA can be found in the Abyssinian. The first is an autosomal dominant early onset form of PRA that is passed directly from one generation to the next and is fortunately rare. The second is an autosomal recessive middle-age onset form that is relatively prevalent in Scandinavia, the UK and the US. This type of middle-age onset PRA is characterised by progressive degeneration of both rod and cone cells in the retina and has been designated “rdAc”. It is believed that a single mutation in a gene called CEP290 produces a defective protein, which is associated with this type of feline PRA. Cats affected with this form of blindness have normal vision at birth, with retinal degeneration first detectable by electroretinography at about 7 months of age, although symptoms do not develop until later. Visual loss progresses slowly and is variable, with most cats developing symptoms and/or blindness by usually 3-5 years of age. This is an autosomal recessive condition, thus the disease is not associated with gender and two copies of the mutation (one from each “carrier” parent) are required for the cats to lose their vision. Carriers, i.e. cats that have one copy of the mutation, are not affected and have normal vision.

In addition to the Abyssinian, Somali and Ocicat, a survey of 43 cat breeds showed the presence of the CEP290 mutation in many other breeds including the American Curl, American Wirehair, Bengal, Balinese, Colourpoint Shorthair, Cornish Rex, Munchkin, Oriental Shorthair/Longhair, Peterbald, Siamese, Singapura and Tonkinese. The high frequency of the CEP290 mutation in Siamese (about 33%) and related breeds (Oriental Shorthair/Longhair, Balinese, Colourpoint Shorthair, Peterbald) poses a potentially significant health risk in the Siamese (and Oriental) breed groups.

Symptoms of PRA

The initial changes in PRA are a loss of rod cells leading to night blindness followed by a slower loss of cone responses and progressive deterioration in daytime vision. The age at onset and rate of progression may vary, but typically affected cats are unlikely to show symptoms before the age of 3-5 years, i.e. well past the time that breeding stock have already passed on their genes to the next generation(s). Most cats develop symptoms only in the late stages of disease because they compensate very well as their vision slowly deteriorates. Sometimes the blindness can appear to owners to be sudden in onset, even though it has been developing for months, because the cat may show almost no signs until the last bit of vision has been lost.

Owners may first notice a change in personality of an affected cat such as reluctance to go down stairs or down a dark hallway. This is characteristic of night blindness, in which vision may appear to improve during the daytime. As the disease progresses, owners can observe a dilation of the pupils and an increase in the reflection of light from the back of the eye. If the blindness is progressing slowly, the owner may not notice any signs until the cat is in unfamiliar surroundings and the lack of vision is more apparent. In some animals, the lens of the eye may become opaque or cloudy as a secondary cataract develops as a later complication (sometimes mistakenly assumed the primary cause of the vision loss).

The key things to watch for are:

- Cat with dilated pupils.

- The cat is bumping into objects, reluctance to jump up onto surfaces or reluctance to go outside, especially in dim light or darkness.

- More readily visible eye shine from the back of the eye due to dilation of the pupils.

How is PRA Diagnosed

Formal veterinary investigations, which may include referral to an ophthalmology centre, are needed to diagnose PRA and to exclude other diseases that may present with poor vision in cats. Your local vet will therefore need to take a complete medical history and perform a thorough physical examination of any cat presenting with loss of vision and should always be your first port of call for any cat displaying symptoms suggestive of PRA.

As PRA is non-painful, on external examination the outward appearance of the eye is often normal, i.e. no redness, excess tearing or squinting. Characteristic changes in the retina and other parts of the eye may be observed through an ophthalmic examination by a veterinary opthalmologist. More sophisticated tests such as electroretinography may also be used, especially to assist in early diagnosis or to confirm that the origin of the problem is indeed in the retina. Both tests are painless and the cat does not usually have to be anaesthetised. It is now also possible to perform a genetic test for PRA in cats (see below).

Ophthalmoscopic examination typically reveals a sluggish light reflex (normally there is rapid constriction of the pupil when light is shone directly into the eye) and possibly secondary cataract. On retinal examination, in the early stages of PRA a granular appearance affecting the peripheral retina may be observed and as the condition progresses typical signs of a generalised retinal thinning become apparent. There is hyper-reflectivity of the tapetum, loss of the superficial retinal blood vessels and then in the later stages pigmentary changes elsewhere in the retina and atrophy of the optic nerve. These changes are bilateral and similar between the two eyes.

PRA can sometimes be confirmed at the time of retinal examination because of these characteristic changes in the appearance of the retina. However, the early stages of the disease can be more difficult to diagnose, and in that instance the disease can be detected with an electroretinogram, which measures the electrical responsiveness of the retina, to evaluate the function of the photoreceptor cells when they are stimulated with flashes of light. If the electroretinogram is abnormal, then the retina is diseased. If the electroretinogram is normal, then the origin of visual loss is somewhere other than the retina.

If your vet is concerned that some disease other than PRA is the source of the cat’s loss of vision, then tests to rule out other causes may include the following:

- A full blood count and renal/hepatic function tests.

- A feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) test, a feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) test and a toxoplasmosis titre to look for the presence of these infectious causes of visual loss.

- Plasma or blood taurine levels (taurine deficiency may be associated with blindness in cats).

- A measurement of systemic blood pressure to rule out hypertension.

- Chest and abdominal X-rays.

Genetic Testing for PRA

To assist in identifying affected, carrier and normal cats, DNA tests are also now available from various laboratories. These tests use DNA collected from cheek swabs and can identify the PRA status of the cat without the need for blood tests or any other formal veterinary examination. These genetic tests can be used as tools by breeders to inform breeding decisions and prevent the birth of affected (and/or carrier) offspring; and also by owners and vets to confirm a diagnosis of PRA in cats showing signs of the disease.

One laboratory, Langford Veterinary Services, has recently published the results of their genetic testing for PRA conducted in certain breeds of cat (see table below). This makes for rather disturbing reading as these results suggest that the problem of PRA in the UK is more prevalent among Oriental and Siamese breeds than in all other breeds known to be associated with the disease.

|

Normal |

Carriers (Heterozygotes) | Affected (Homozygotes) | |

| Abyssinian | 27 (60%) | 17 (38%) | 1 (2%) |

| Ocicat | 31 (84%) | 6 (16%) | 0 (0%) |

| Somali | 20 (62.5%) | 12 (37.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Oriental | 46 (43%) | 51 (48%) | 10 (9%) |

| Siamese | 26 (62%) | 11 (26%) | 5 (12%) |

However, several things should be borne in mind when trying to interpret the meaning and significance of these results. Firstly, there are only very small numbers of cats tested, which automatically introduces the possibility of statistical bias. Secondly, the cats tested will have been tested for a reason, e.g. the owner/vet suspects either that they have the condition or that they are at risk of the condition or carrying PRA. These results, therefore, are subject to selection bias and are unlikely to be representative of the general population of Oriental and Siamese cats in the UK. Thirdly, consultation and referral rates for clinical cases of Oriental and Siamese cats with suspected PRA in no way reflects the figures seen above and in clinical practice PRA in Oriental and Siamese cats is rare.

There are several possible explanations for the apparent mismatch between the high frequencies of PRA gene mutations presented above, and the observed low clinical frequency of cases of PRA in Oriental and Siamese cats:

- The DNA test is unreliable in Oriental and Siamese cats and has a high rate of false positive results.

- The DNA test is not applicable to Oriental and Siamese cats with PRA.

- A different genetic mutation, or more than one genetic mutation, is involved in PRA in Oriental and Siamese cats.

- The faulty gene has incomplete or variable penetrance and requires the interaction of other factors (different genes, environmental factors, etc) to cause the clinical manifestations of PRA in Oriental and Siamese cats.

- Oriental and Siamese cats may have a different expression of the disease than in other breeds of cat and instead of developing blindness due to PRA by age 3-5 years, blindness develops at a much later age. Indeed, many Oriental and Siamese cats affected by PRA may therefore die from other causes before they reach an age sufficiently old enough to manifest the symptoms of PRA and develop blindness. For affected Oriental and Siamese cats living into old age, blindness may therefore develop only after age-related decline in body condition and function make visual loss and blindness very hard to detect, which is why there are so few cases of PRA presenting clinically to vets.

- Any combination of the above.

Treatment of PRA

Unfortunately, there is no treatment for PRA, nor a way to slow the progression of the disease and cats showing signs of PRA usually become blind over time (months to years). However, cats are remarkably adaptable to progressive blindness, and can often seem to perform well in their customary environments.

Living with a Blind Cat

For cats as with humans, the onset of blindness represents a life-changing event. Nevertheless, cats are more than capable of adapting to a new lifestyle and, especially when blindness develops gradually as is the case with PRA, they usually continue to enjoy happy and fulfilling lives. However, blind cats do require specific considerations by their owners.

Blind cats rely on scent, memory and spatial orientation to navigate. As long as their environment is kept constant they usually cope well, but changes to their known environment may confuse and upset them – for example, if their litter tray is moved to a new location, a blind cat will have trouble finding it. The same applies to food and water bowls. Rearranging furniture may also be problematic for a blind cat. Not only will the cat start walking into the rearranged tables and chairs, but these objects also carry scent beacons by which the cat navigates. Cats mark their territory by rubbing their head and cheeks on the furniture, walls and other household fittings. The rubbing releases a small amount of facial pheromone from the glands in the cat’s cheeks. With a sighted cat, these are territorial markers, but with a blind cat, the scent of the different markers allows them to work out their position within their territory. Similarly blind cats may have difficulty coping if floors become untidy or cluttered with temporary objects.

Free roaming access to the outdoors is not recommended for a blind cat, not only because the outdoor environment is less controllable, but because of the danger of the cat becoming lost. If a cat explores beyond its territory, smell and scent beacons can no longer can guide them home. In this situation, a blind cat is both lost and highly vulnerable. However, a blind cat need not always be an indoor cat as it may be possible to fence off part of the garden where the cat can be safe. In addition, cats can be trained to use a harness or a lead, which may make outdoor exercise enjoyable and safe for a blind cat.

The indoor play may also need to be adapted to stimulate cats other senses, especially smell and hearing. A ball rolling on the floor will hold little interest for a blind cat, but a ball with a bell inside can now become an attractive toy. Scattering a blind cat’s favourite treats or biscuits on the floor will challenge them to find them by smell. Some owners like to talk to a blind cat when they approach them so the blind cat can easily recognize the direction of the approach (although they will be acutely aware of approaching footsteps) and that it is being made by someone they know and trust.

Some owners may feel the urge to pick up a blind cat and carry them from one place to the next. Carrying a blind cat will certainly move them safely from A to B, but it actually does a blind cat no favours. Studies have shown that cats are egocentric – they literally orientate the world in relation to themselves. So when you pick up a blind cat and move to a new location their whole navigation system becomes disrupted, resulting in a confused and stressed cat. If you do carry a blind cat, make sure the journey finishes somewhere they can immediately map into their mental landscape, such as their bedding or litter tray. Also, do not put a blind cat on raised furniture unless they are familiar with where they are, e.g. their favourite chair, otherwise they may fall off.

Future Options for the Protection of Orientals and Siamese from PRA

As there may still be much to learn about the transmission and expression of inherited forms of PRA in the cat, there may not yet be a definitive answer as to how best to manage this condition at the present time. However, the following options are worthy of consideration and will be discussed alongside their relative advantages and disadvantages:

- Selective breeding to eliminate the PRA gene mutation from the general population of Oriental and Siamese cats. Given that a DNA test for PRA is available it is, in theory, possible to test all potential studs and queens prior to breeding for the presence of the PRA mutation and to exclude all affected cats and all carriers from breeding programmes. If every breeder were to commit to this, the inherited PRA mutation of the CEP290 gene responsible for feline PRA could potentially be eliminated from the general population of Oriental and Siamese cats within two to three decades. However, it is unlikely that all breeders would undertake this commitment, which also has the major disadvantage of placing significant restrictions on the size of the gene pool in an already vulnerable population of cats. Furthermore, if the currently available genetic tests for feline PRA are subsequently proven to be unreliable (for which there are several precedents for ‘new’ genetic tests in other areas and species) this measure, which could be expected to exclude around half of Oriental and Siamese cats from breeding programmes, would have been completely unnecessary. Neither would this approach have any impact on the development of spontaneous genetic mutations giving rise to PRA. For all the reasons stated above, it is unlikely that this approach will enhance the Oriental and Siamese breeds and should therefore be discarded.

- Selective breeding to avoid the creation of cats homozygous for the PRA gene mutation. Again, given that a DNA test for PRA is available it is, in theory, possible to test all potential studs and queens prior to breeding for the presence of the PRA mutation. However, with this approach no cats are excluded from breeding programmes, but affected cats and carriers are mated only to normal cats so that no affected offspring result. However, again it is unlikely that all breeders would undertake this commitment, which also has the disadvantage of reducing the genetic diversity of potential future matings and the number of normal cats in the general population is likely to decline. Again, until the accuracy and validity of the available DNA tests in Oriental and Siamese cats and the clinical consequences of these test results can be confirmed this may be a negative approach, although many responsible breeders are starting to voluntarily adopt this policy in an attempt to avoid breeding offspring affected by PRA. Again, this approach would have no impact on the development of spontaneous genetic mutations giving rise to PRA.

- Changes to breeding policies. For all the reasons stated above, there is insufficient robust data on PRA in Orientals and Siamese to contemplate a change to the breeding policies of these breeds at this time. In addition, these breeding policies are only ever recommendations and cat breeding can never be ‘policed’ to ensure compliance with such guidelines. However, this does help raise awareness and allow breeders to make informed decisions regarding their breeding practices.

- Further research. This would seem an obvious way forward as one thing we can be sure of regarding PRA in Oriental and Siamese cats – without more research we will never confirm if this ‘problem’ is real or not or its magnitude in our breeds. However, to be of value, studies need to be of robust design and avoid the potential pitfalls discussed above, especially with regard to the introduction of bias into their design. It will certainly help raise awareness of PRA in Orientals and Siamese breeds to encourage breeders to test their cats and to share and pool their results, but to be of scientific value what we need to understand is the true prevalence of the PRA gene mutation in the general population of Oriental and Siamese cats, which can only be accurately determined by randomised selection for testing. It is also important to determine how many of those that do test positive using the available DNA tests go on to develop the symptoms of PRA and blindness in later life and at what age this happens in Orientals and Siamese. This information will also provide an opportunity for additional validation of the available genetic tests for PRA.

Conclusion

Visual loss and blindness in cats thankfully rare, but PRA is one recognised hereditary cause. It is now possible to perform genetic testing to identify the gene mutation believed to be responsible for PRA in cats, although the reliability and significance of these test results remain to be confirmed in Oriental and Siamese breeds. Until robust data exist that addresses these uncertainties it is difficult to identify a recommended way forward in terms of breeding policies, although some breeders are already voluntarily testing their breeding stock and potential breeding stock and using this information to inform breeding decisions so as not to risk producing offspring affected by PRA. The outcome and consequence of these decisions based exclusively on a relatively new genetic test in an already vulnerable gene pool is yet to be manifest. This article serves to highlight the issue of PRA in Oriental and Siamese cats and the urgent need for further robust and well-designed research in this area.

Members of the Oriental Cat Association can obtain a 20% discount on all genetic testing offered by Langford Veterinary Services. Please contact Irene Rothwell to obtain the promotional code via the contact page.